Early translations of the Xiangqi (Chinese Chess) Pieces Part 2

Author: Jim Png from XqInEnglish

This article would be a continuation of the previous article where the author has studied and located the ancient English texts for early translations of the names of the Xiangqi pieces in Chinese.

1891AD Z. Volpicelli's description

1893AD Henry Bird mentions the pieces

1893AD W.H Wilkinson published a Manual of Chinese Chess

1895AD Stewart Culin introduced Xiangqi in Chess and Playing Cards

1913AD HJR Murray and his A History of Chess

Summary Tables of Various Translations used in the Past by English Writers

Different culture, different emphasis

Preserving the original history and culture

Romanization vs. Direct Translation vs. International Chess Terms?

1891AD Z. Volpicelli's description

Z. Volpicelli is the next writer to be mentioned. In 1888, he published an article called Chinese Chess which was quite an in-depth discussion on the technical aspects of Xiangqi. The author was able to buy Z. Volpicelli's work online from Google. Unfortunately, pages 255 and 256, which the author suspects to be an introduction to the Chariot and horse, were missing in the book.

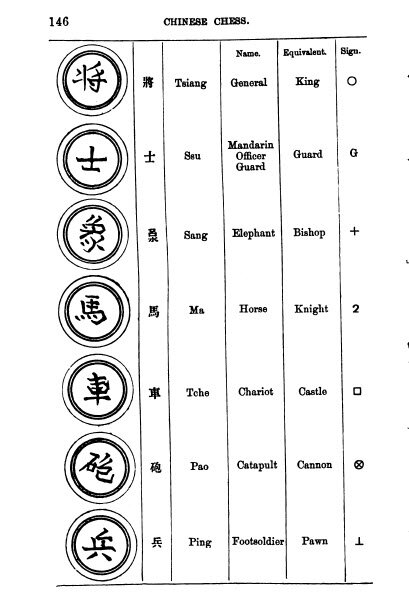

As for the pieces, instead of writing the Chinese characters on the pieces, Volpicelli used Roman numerals to represent them. The Red pieces were embossed while the Black pieces were debossed. He would add a short paragraph to each example he used in the book, showing the representation of each piece. The following is the key used in his book:

I for King,

II for Minister Advisor),

III Bishop (Elephant),

IV for the Knight,

V for the Rook,

VI for the Cannon, and

VII for the Pawns. (1 p. 252)

Note: Volpicelli mentioned another earlier article written in 1866 by Hollingworth that also introduced Xiangqi. Unfortunately, the author has not been able to identify the article.

1892AD Falkner's book

Edward Falkener published his book, Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, in 1892. (2)

His translated terms were similar to his predecessors. What was unique about Falkener's work was that he had symbols for the pieces, which were probably his own inventions. His notation system used coordinates and he was able to describe a few games. He also mentioned several 'Chinese' terms which the author suspects to be a dialect, probably Cantonese or Hokkien.

1893AD Henry Bird mentions the pieces

Henry Bird's Chess History and Reminiscences essentially dealt with his study of history as he plowed through the works of his famous predecessors. The names he used for the Xiangqi pieces were basically lifted from these early predecessors and will not be discussed in detail in this article. (3)

1893AD W.H Wilkinson published a Manual of Chinese Chess

Sir William Henry Wilkinson (1858 – 1930 AD) was a Consul-General for Great Britain. He was also a sinologist who had served as acting consul-general and eventually Consul-General to several places in China and also Korea. With regards to Xiangqi, he published A Manual of Chinese Chess in 1893.

Unfortunately, this book has been one of the unicorns that the author has had trouble locating. There was some hope for the book as it was said that it could be found in an English library. Unfortunately, the author can only wait until the pandemic is over before he is able to continue his quest for the book.

1895AD Stewart Culin introduced Xiangqi in Chess and Playing Cards

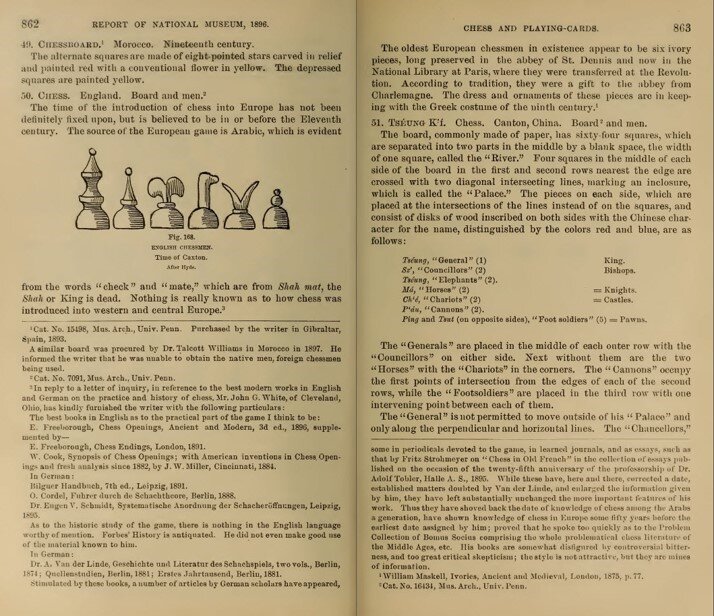

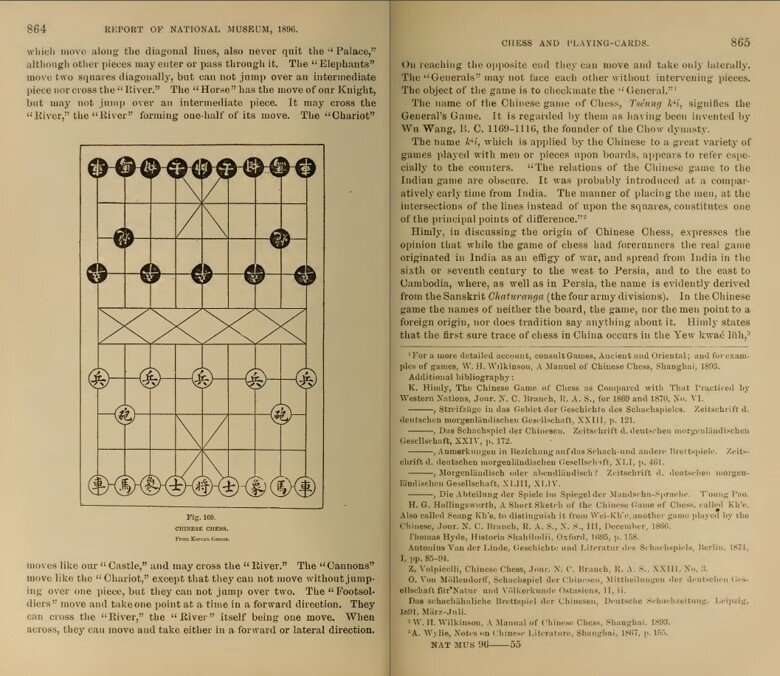

The next Western work on Xiangqi was by Stewart Culin who authored the book Chess and Playing Cards. (4 pp. 863-864)

Steward Culin's work was groundbreaking in his time for he was the first to correlate Xiangqi with divination.

1913AD HJR Murray and his A History of Chess

Harold James Ruthvens Murray (1868 – 1955 AD) was perhaps the most influential Western scholar on the topic of the history of chess. His views on the history and origins of Xiangqi are also very well-received in the West. (5)

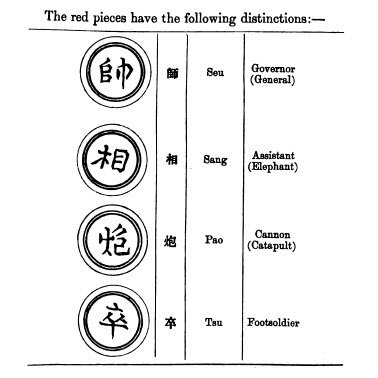

Murray's writings are too much for this short article. Instead, we will focus on his translations. Murray tried to stem his authority on several issues. One of them was the fact that the Red and Black pieces were not to be called the same. He also correctly translated the Chinese of the 'palace' as nine Castle. In Chinese, it would be 九宮 or nice palace/room.

However, his translation as 'assistant' for the Red Elephant could result in confusing the Advisor for the Elephant piece.

Modern-day Translations

In the twentieth century, there were more and more books that were written about Xiangqi.

In 1974, Terrence Donnelly wrote Hsiang Chi The Chinese Game of Chess. In his book, which comes with its own foldable chessboard and pieces, the names of the Xiangqi pieces were: General, Mandarin (for the Advisor), Elephant, Horse, Chariot, Cannon and Soldier. (6)

HT Lau's Chinese Chess An Introduction to China's Ancient Game of Strategy was published in 1985. Despite several inadequacies, it has remained one of the most popular and perennial best sellers for books on Xiangqi, in English. For the pieces, Lau used the following translations: King (General), Rook (Chariot), Cannon, Knight (horse), Counsellor, Minister (for Elephant) and Pawn/Foot soldier. (7)

In 1987, in an attempt to promote figurine pieces, the Singapore Chinese Chess General Association (now known as Singapore Xiangqi General Association, SIXGA), a booklet was published. The chief editor was the late Mr. Chan Fook Loi. For the pieces, the following translations were used: King, Assistant, Chariot, Gunner (for Cannon), Horse, Elephant and Pawn.

In 1989, Sam Sloan published his Chinese Chess for Beginners. There were two further reprints in 1992 and 2006. In his book, he mentioned that the Asian Chinese Chess Association (which should be the Asian Xiangqi Association), previously named the pieces as follows: Chariot, Horse, Elephant, Assistant, Gunner, Pawn and King. Later, they dropped Chariot in favor of rook and gunner in favor of Cannon. However, in his book, Sloan chose to call the pieces rook, knight, bishop, guard, Cannon, pawn and King. (8 pp. 10-11)

Summary Tables of Various Translations used in the Past by English Writers

Before beginning to introduce the various translations, the author has spent hours compiling the table shown below. It would be a rough introduction to how the early writers had translated the terms.

|

WXF names |

Matteo Ricci 1583-1610AD |

Alvaro Semedo 1613-1636AD |

Shen Fuzong & Thomas Hyde |

Robert Lambe 1765AD |

|

King |

kingpiece |

King |

ciang/cai |

general |

|

Chariot |

cu |

chariot/wagon |

||

|

Horse |

knights |

ma/ba |

knight |

|

|

Cannon |

gunpowder bowls/catridges |

Vasi di Polvere / vessls of duft |

pao |

cannons |

|

Pawn |

pawn |

Pawnes |

ping/co |

pawns |

|

Advisor |

Bishop! |

su |

lieutenant-generals |

|

|

Elephant |

bishop |

siang 象elephas and siang Assitens |

elephant |

|

|

River |

kia ho |

kia ho/ river |

||

|

Palace |

four squares contiguous to his original position |

four nearest places to his own Station |

tent/palace |

|

WXF names |

Eyles Irwin 1793AD |

Hiram Cox 1799AD |

Augustus Lindley 1866 |

K. Himly 1870AD |

|

King |

King/Chong |

king/choohong/generalissimo |

king |

chiang Shuai |

|

Chariot |

war chariots/tche |

tche/war chariots/rooks/castles |

castle |

chariot/castle/chu |

|

Horse |

knights/Mai |

Mai/horse/cavalry |

knight |

horse |

|

Cannon |

rocket boys / pao |

paoo/artillery/rocket man |

gun |

cannon/pao |

|

Pawn |

pawns/ping |

ping/foot soldiers |

pawn |

ping |

|

Advisor |

Princes/Sou |

counselor or soo |

mandarin/shield |

shi/secretaries |

|

Elephant |

Mandarins/Tchong |

tchong/elephant |

bishop |

Hsiang |

|

River |

river |

hoa ki/trench |

ditch |

|

|

Palace |

fortress |

fort |

nine points |

|

WXF names |

JD Vaughan 1879AD |

HFW Holt 1885AD |

Z. Volpicelli 1891AD |

Falkener 1892AD |

|

King |

captain/king |

General / King |

King |

King/General |

|

Chariot |

carriage / castle |

Chariot/ Chē |

rook |

chariot |

|

Horse |

horse |

Horse/Ma |

knight |

Horse |

|

Cannon |

cannon |

P'ao/Cannon/Ballista |

cannon |

guns/catapults |

|

Pawn |

soldier/pawn |

Soldier / Ping or Ts'uh |

pawn |

footsoldier |

|

Advisor |

scholar / councillor |

Minister / Sze |

minister (advisor) |

Guard |

|

Elephant |

elephant |

Elephant/Seang |

bishop / elephant |

Elephants |

|

River |

river |

river |

river |

|

|

Palace |

citadel |

general's squares or quarters |

palace |

fortress |

|

WXF names |

Stewart Culin 1895AD |

HJR Murray 1913AD |

Donnelly 1974AD |

HT Lau 1985AD |

|

King |

General/Tchong |

General for Black King / Governor for Red King |

General |

King/General |

|

Chariot |

Chariots/Cu |

Chariot |

Chariot |

Rook/Chariot |

|

Horse |

horse |

horse |

Horse |

Cannon |

|

Cannon |

cannon |

cannon / catapult |

Cannon |

Knight/Horse |

|

Pawn |

foot soldiers/ping/tsuh |

foot soldier |

Soldier |

Counsellor |

|

Advisor |

councillor |

Counsellor |

Mandarin |

Minister/Elephant |

|

Elephant |

Elephants |

Elephant for Black Elephant/Assistant for Red Elephant |

Elephant |

Pawn/Foot |

|

River |

river |

river |

river |

river |

|

Palace |

palace |

nine Castle |

king palace |

|

WXF names |

Singapore Chinese Chess Association 1987AD |

Sam Sloan 1989AD |

|

King |

King |

King |

|

Chariot |

Chariot |

rook |

|

Horse |

Horse |

knight |

|

Cannon |

Gunner |

cannon |

|

Pawn |

Pawn |

pawn |

|

Advisor |

Assistant |

guard |

|

Elephant |

elephant |

bishop |

|

River |

||

|

Palace |

Some thoughts

As can be seen, the translations for the same Xiangqi piece could be varied and sometimes even interesting. For example, the Advisor has been called the lieutenant general, minister, councillor, prince, secretary et cetera.

Early attempts at romanization of the Xiangqi pieces also led to some confusion as the early Western Xiangqi writers did not not know the dialects in China. And because of thick heavy accents in reading the Chinese, they probably sounded different and were thus 'romanized' differently.

There are several issues with naming of the pieces.

Different culture, different emphasis

To begin with, there is a need for the pieces in Xiangqi to be able to 'renamed' such that they could discussed and written in another language, for example, in English. It would perhaps be the most important step in the promotion of Xiangqi. To make Xiangqi more 'user-friendly', the translations would have to be something non-Chinese players can understand and get accustomed to very rapidly.

Hence, it was natural for early translators to adopt the names of the pieces in Xiangqi.

As Sam Sloan put it in his book,

"Westerners tend to use the same names which are familiar to them from International Chess. Chinese tend to use the word which is the direct translation of the name of that piece from Chinese to English. Thus, the piece which starts in the corner and has the power to move and capture vertically and horizontally is called the 'rook' by Westerners, but the Chinese usually call it either the 'chariot' or the 'car'. The reason for this is that the Chinese character for that piece is also the word for automobile in modern Chinese."

Preserving the original history and culture

However, when choosing the names of these new translations, the original cultural identity and history associated with the piece must also be transmitted and preserved in a foreign language.

Hence, translations like lieutenant general for the Advisor, or rocket boy for the Cannon are simply unacceptable.

Romanization vs. Direct Translation vs. International Chess Terms?

There were several early attempts by Western scholars to romanize the Xiangqi pieces. For example, calling the Cannon a Pao. It would appear to work at first…BUT, people of different languages tend to pronounce the same word differently. Imagine a person with a thick accent pronouncing the same word as compared to a person with a thin accent. Or a Texan pronouncing the same word as compared to a person with an Irish accent. The resulting 'romanization' could be confusing.

And the problems with romanization do not end there. There are many dialects in China and as can be seen from the example with Eyles Irwin's translation and Cox's translations, romanization cannot work because the dialects were different in the first place!

Direct translations would seem to be the next solution. Unfortunately, the linguistics of the Chinese language would make things extremely complicated. Each piece can have more than one meaning in Chinese, and so, which meaning would be translated? Early Western scholars like Himly, Holt, van der Linde, Mollendorf et ctera have tried their best to identify the Chinese passages and translate them. 象 can mean Elephant, figure, phenomena et cetera. Coupled with the fact that several Xiangqi pieces have different Chinese characters when they are in different colors would compound the problem.

Using International Chess Terms would appear to be the final solution…?! But, calling the Elephant a bishop just does not seem right! And the Horse piece in Xiangqi is not entirely the same as the Knight.

The issue of abbreviations

Many writers have gone ahead and translated the terms to their own likes and preferences. And some have been quite good. But, as with any language, it has to be practical.

More often than not, the names of the translated pieces are okay, but the trouble would occur when using the abbreviations when recording scores. For example, if you were to call the Advisor a Counsellor, what would its notation be? A4+5 would be simple, but if you used C4+5, then would the Cannon have to change its abbreviation?

That is one reason why the Rook would be a better replacement than the Chariot in this instance as the abbreviation would be 'R'. However, the author agrees with using the Chariot, and stating that its abbreviation is 'R' as it would better reflect the historical entity of Zi Che 辎车 (zī chē) which is supposed to have been the precursor of the Chariot piece.

And if both colors used the same English translation, it would cause less trouble during writing the scores. For example, although 'Minister' would be better for the Red Elephant, it would seem awkward when writing the scores. M3+5 for Red, but E3+5 for Black? There is more than meets the eye!

WXF Rules: the official standard

In 2017, the WXF Rules was finally published which officially recommended the terms: King, Advisor, Elephant, Chariot, Horse, Cannon and Pawn for the pieces of both colors. The author was honored to have done the English translation of the rules. He firmly believes that an official set of terminology would be the best for this early stage of promotion of Xiangqi. Speaking a common language, the language of Xiangqi would be beneficial for the promotion of the game.

No doubt, there are inadequacies to the names of the pieces. For example, the author believes that the catapult would be a better translation for the Black Cannon which has the radical for stone. But, for the moment, he is satisfied with working with a defined set of official rules. Changes can be made later and minor adjustments corrected.

Final thoughts

To promote Xiangqi, the worst thing that can happen is when different people speak a different language. The flow of ideas cannot happen and there would not be any discussion. A universal set of terms must be present for Xiangqi to flourish in a different culture or environment.

Works Cited

1. Volpicelli, Z. Chinese Chess. Journal of the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1888, Vol. Vol. XXIII, No. 3, p. 248/284.

2. Falkener, Edward. Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them. London : Longmans, Green and Co, 1892.

3. Bird, HE and Wikisource contributors. Chess History and Reminiscences. Wikisource. [Online] Oct 31, 2019. [Cited: Oct 31, 2019.] https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Chess_History_and_Reminiscences&oldid=6991981.

4. Culin, Stewart. Chess and Playing Cards. Atlanta : s.n., 1895.

5. Murray, HJR. A History of Chess ( 1913 Orginal Edition). New York : Skyhorse Publishing, 2012. reprint. 978-1-63220-293-2.

6. Donnelly, Terrence. Hsiang Chi The Chinese Game of Chess. Sussex : Wargames Research Group, 1974. p. 74. No ISBN given.

7. Lau, H.T. Chinese Chess An Introduction to China's Ancient Game of Strategy. Singapore : Tuttle Publishing, (Asia Pacific: Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd), 1990. 978-0-8048-3508-4.

8. Sloan, Sam. Chinese Chess for Beginners. California : The Ishi Press., 1989. 0-9239891-11-0.

9. Li, David H. The Genealogy of Chess. s.l. : Premier publishing, 1998. 0-9637852-2-2.

10. Himly, K. The Chinese Game of Chess as Compared with that Practised by Western Nations. Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1869 & 1870, New Series No. VI, pp. 105-122.

11. Holt, H.F.W. Notes on the Chinese Game of Chess. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 17, Jul 1885, Vol. 3, pp. 352-365.

12. Keats, Victor. Chess Its Origin Vol. II A Translation with commentary of the Latin and the Hebrew in Thomas Hyde's De Ludis Orientalibus (Oxford, 1694). Oxford : Oxford Academia Publisher, 1994. 1899237011.

13. Gallagher, Louis J. China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matthew Ricci: 1583-1610. [trans.] Louis J. Gallagher and Trigault. New York : Random House, 1953.

14. Semedo, Alvaro. The History of That Great and Renowned Monarchy of China. London : John Crook, 1655.

15. Poole, William. The Letters of Shen Fuzong to Thomas Hyde, 1687-88. Electronic British Library Journal. 2015, eBLJ 2015.

16. Hyde, Thomas. De ludis Orientalibus. s.l. : e theatro Sheldoniano, 1694. p. 277. Vol. 2.

17. Lambe, Robert. History of Chess, Together with Short and Plain Instructions, By which any one may easily play at It without the Help of a Teacher. Original London. Reproduction by Harvard University Houghton Library : ECCO Eighteenth Century Collections Online Print Editions, 1765AD. ESTCID: NO17486.

18. Ponziani, Domenico Lorenzo; Dal Rio, Ercole; Irwin, Eyles. The Incomparable Game of Chess: Developed After a New Method of the Greatest Facility, from the First Elements to the Most Scientific Artifices of the Game. [trans.] J.J Bingham. s.l. : J.J. Stockdale, 1820, 1820. p. 340.

19. Irwin, Eyles. An Account of the Game of Chess, as Played by the Chinese, in a Letter from Eyles Irwin, Esq; to the Right Honourable the Earl of Charelmont, President of the Royal Irish Academy. The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy. 1793, Vol. 5, pp. 53-63.

20. Lindley, Augustus Frederick. Ti-ping tien-kwoh: The History of the Ti-Ping Revolution, Including a Narrative of the Author’s Personal Adventures. London : Day & Son (Limited), 1866.

21. Cox, Hiram. Burmha Game of Chess compared with The Indian, Chinese, Persian Game of the Same Denomination. Asiatic Researches. 1807, Vol. VII, p. 486. Paper delivered 1799, published several times posthumously.

22. Vaughan, J.D. The Manners and Customs of the Chinese of the Straits Settlements. Singapore : Mission Press, 1879.