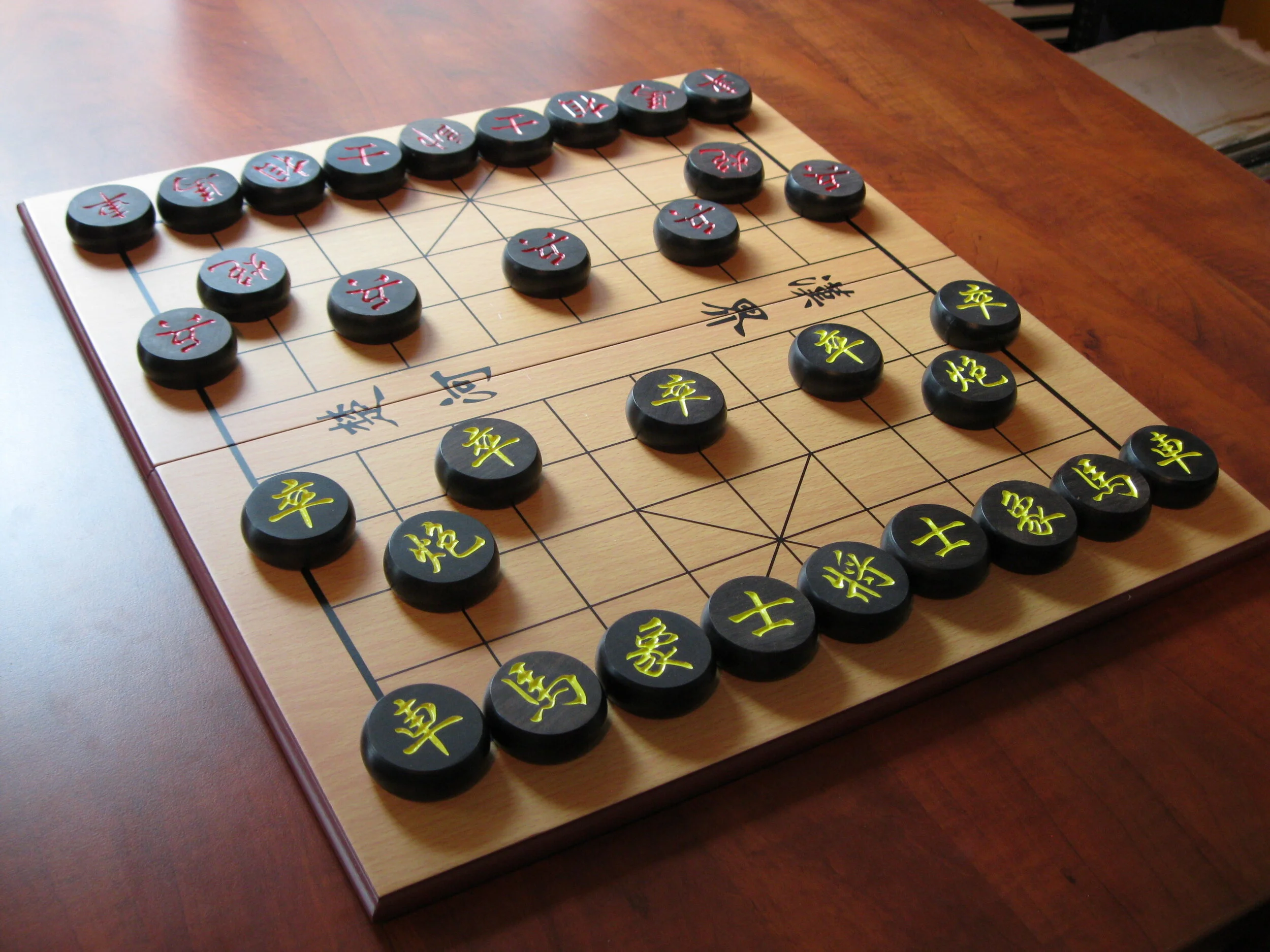

Origins of Xiangqi (Chinese Chess) 10: Red & Black, Royal Rule etc. explained

Author: Jim Png from XqInEnglish

This article would be a continuation of previous article on the Chu-Han Contention discussing the possible origins of the history of Xiangqi. It will discuss the various ‘phenomena’ of Xiangqi with relation to the Chu-Han Contention. For example, why are the colors Red and Black used, why does Red move first, how the Royal Rule came about, et cetera will be discussed.

The history of the possible origins of Xiangqi prior to the Qin Dynasty has already been covered in earlier articles which can be found on the website under the section of the history of Xiangqi.

In this article, the contents will be as follows:

The equilibrium in the game of Xiangqi

Why are the colors Red and Black used in Xiangqi?

Why does Red move first in Xiangqi?

Why does the King in Xiangqi not allowed to meet each other face to face in the same file?

Why the Pawns cannot retreat after crossing the river?

The author also managed to find a few Youtube videos discussing depicting the important events during the Chu-Han Contention that includes some of the historical incidences mentioned below. A timeline of the related events has been presented by the author to refer to the various incidents that will be discussed in this article.

The link to the first Youtube video, in English, is:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FlVXwef66bA

The related contents to this article, on the time of the videos are:

About 2:00, Xiang Yu watching the Qin army (the color Black).

5:35: Incident of Liu Bang slaying the White Snake.

8:45: Liu Bang choosing the color Red to represent himself.

15:00: Xiang Yu crosses the river, smashed the cauldrons and sank the boats.

The link of the second video is:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FbtKEICVv9M&list=PLTWtVUzAvZ3oUSBoHO8-NwMofWR2tdUfK&index=3

0:30, historical incident used to explain why Red moves first.

4:00, possible origins of the Royal Rule.

The equilibrium in the game of Xiangqi

Many Chinese people believe that Xiangqi was invented to mirror the Battle at the Hong Canal during the Chu-Han Contention. Both warring factions were at a standstill and neither party could get the upper hand. The Battle at Hong Gou lasted for about two years and neither side could get the upper hand. Xiang Yu was running out of supplies but he had held Liu Bang’s father and other family members as hostage.

As a result, a truce was negotiated with Xiang Yu releasing Liu Bang’s father and other family members in 203BC. It was known as the Treaty at Hong Gou. There have been some arguments by the historians as to who initiated the truce. Although the Records of the Grand Historian clearly suggested that it was Liu Bang who initiated the truce, there have been opposing voices. However, it would be beyond the scope of this article to discuss it.

There were many passages that mentioned the incident in the ancient books. The most notable ones would be from the Records of the Grand Historian which are given below whereby it was mentioned more than once. Other important books that mentioned the incident include the Book of Han and Tai Ping Yu Lan which had similar mention and will not be included here.

《史記·高祖本紀》

當此時,彭越將兵居梁地,往來苦楚兵,絕其糧食。田橫往從之。項羽數擊彭越等,齊王信又進擊楚。項羽恐,乃與漢王約,中分天下,割鴻溝而西者為漢,鴻溝而東者為楚。項王歸漢王父母妻子,軍中皆呼萬歲, (1)

Diagram 1 The Equilirum in Xiangqi, Picture courtesy of Rick Knowlton of AncientChess.com.

As mentioned above, the River on the Xiangqi board is believed to be the Hong Canal where the Treaty of the Hong Canal was signed. The territory West of the Canal belonged to Liu Bang (Han) while the territory East of the Canal belonged to Xiang Yu (Chu). Neither side could gain the upper end, much less defeat their archenemy at the time the truce was signed.

As mentioned in the previous article, modern day historians like Zhou Jiasen have attributed the river to be the Hong Canal.

周嘉森 《象棋與棋話》

漢韓信伐趙時,作象棋,及葉子戲以娛士卒,因年終士卒思鄉,一得博具,則相聚共戲,錢財賭盡而忘歸.又 漢畫鴻溝為界,故象棋亦有楚河漢界之分.(西元以前二零六至二零四年) (2 p. 2)

This bit of history is used to explain why Xiangqi is considered to be in a state of equilibrium at the beginning.

Later, Liu Bang would go back on his words and dishonor the treaty which eventually led to Xiang Yu’s downfall and the establishment of the Hand Dynasty.

Why are the colors Red and Black used in Xiangqi?

The colors used to represent the two factions in Xiangqi are also believed to be associated with the Chu-Han Contention.

The color Red is attributed to Liu Bang, who was also known as the Crimson Emperor. The color that represented Xiang Yu’s army was Black.

There is a little bit of history to the colors that are used.

The Color Black

According to history, this had to do with Emperor Qin Shi Huang as mentioned earlier. From the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》 shǐ jì), in the chapter on the Emperor of Qin, it was said that Emperor Qin was fond of the color black and used it to represent his troops.

Chapter on Emperor Qin from the Records of the Grand Historian:

“ … the troops and their flags were all Black.”

《史記·秦始皇本纪》 “…衣服旄旌(máo jīng)节旗皆上黑。” (3)

In an another chapter on Xiang Yu, before he came to power, it was stated that he once witnessed Qin Shi Huang’s soldiers marching in a grand procession. His uncle Xiang Liang (项梁 xiàng liáng) accompanied him.

The Qin soldiers wore Black and Xiang Yu felt like they were like a black dragon meandering the land. Xiang Yu was inspired by the proceeding and vowed to himself that he would one day replace Emperor Qin. This was recorded in the Records of the Grand Historian.

《秦始. 项羽本纪》

“秦始皇帝游會稽,渡浙江,梁與籍俱觀。籍曰:「彼可取而代也。」” (4)

Later, when Chen Sheng and Wu Guang staged an uprising against the Qin Dynasty, Xiang Yu and his uncle, Xiang Liang (项梁 ? -208BC xiàng liáng) would start their own uprising.

The uncle and nephew duo were so successful and charismatic that other rebel leaders like Chen Ying (陈婴 chén yīng) offered their services to him.

《秦始. 项羽本纪》

嬰乃不敢為王。謂其軍吏曰:「項氏世世將家,有名於楚。今欲舉大事,將非其人,不可。我倚名族,亡秦必矣。」 (4)

In a nutshell, Xiang Liang would later die in battle and Xiang Yu inherited his uncle’s ambitions and grow from strength to strength. Xiang Yu would lead his own men to victories, thereby slowly gaining power. The Qin Dynasty would be overthrown and Xiang Yu eventually controlled much of east China. He would also adopt the Black color to represent his troops. This bit of history has been used to explain the color Black in Xiangqi.

Diagram 2 The Color Red in Xiangqi. Picture Courtesy of Rick Knowlton of AncientChess.com.

The Color Red

The explanation for the use of the color Red can also be found in the Chapter of Gaozu in the Records of the Grand Historian.

Liu Bang was thought to have been the Crimson Emperor (赤帝 chì dì). There was a story that one night, Liu Bang was drunk and was passing through a marsh.

The local inhabitants warned him that there lurked a big snake in the marshes. Liu Bang was too drunk to heed the advice and continued to make his way home.

He did in fact cross paths with the snake and managed to slay it and managed to press on. Liu Bang fell asleep after continuing his way some distance later. Not too long afterward, locals went to where the snake had allegedly lived and found an old woman crying in the night. When asked why she was bereaved, the old woman said that her son had been slain. Upon further questioning, the old lady stated that her son was the White Emperor and had turned into a snake. Unfortunately, her son had been slain by the Crimson Emperor.

《史記·高祖本紀》

高祖以亭長為縣送徒酈山,徒多道亡。自度比至皆亡之,到豐西澤中,止飲,夜乃解縱所送徒。曰:「公等皆去,吾亦從此逝矣!」徒中壯士願從者十餘人。高祖被酒,夜徑澤中,令一人行前。行前者還報曰:「前有大蛇當徑,願還。」高祖醉,曰:「壯士行,何畏!」乃前,拔劍擊斬蛇。蛇遂分為兩,徑開。行數里,醉,因臥。後人來至蛇所,有一老嫗夜哭。人問何哭,嫗曰:「人殺吾子,故哭之。」人曰:「嫗子何為見殺?」嫗曰:「吾,白帝子也,化為蛇,當道,今為赤帝子斬之,故哭。」人乃以嫗為不誠,欲告之,嫗因忽不見。後人至,高祖覺。後人告高祖,高祖乃心獨喜,自負。諸從者日益畏之。 (1)

Later, when others told Liu Bang about the old woman and what she said, Liu Bang was pleased that he was called the Crimson Emperor and would later adopt the color Red to represent his troops. Later, Liu Bang would also pay his respects to the ancient Emperor Huang Di and his arch enemy Chi You. The color Red was chosen to represent his offerings. This passage can be found in the Annals on Gaozu in the Records of the Grand Historian.

《史記·高祖本紀》

眾莫敢為,乃立季為沛公。祠黃帝,祭蚩尤於沛庭,而釁鼓旗,幟皆赤。由所殺蛇白帝子,殺者赤帝子,故上赤。 (1)

Why does Red move first in Xiangqi?

The fact that Red moves first was based on the fact that Liu Bang was faster in conquering Guanzhong (关中Guān zhōng).

Some basic history is required.

In the early days of revolution, there was fighting everywhere and the Qin armies had not been completely squashed. In 208BC, then King Kuai of Chu (楚怀王 c. 355 BCE – 296 BCE, Chǔ Huái wáng), promised that whoever was the first to enter Xianyang (咸阳 Xián yáng), the capital of Qin, would be crowned King of the Guanzhong region.

《史記·高祖本紀》

乃踰城見沛公,曰:「臣聞足下約,先入咸陽者王之。 (1)

Xiang Yu, the brave and fearless warrior that he was, took on the main Qin forces and battled his way to victory. Before starting out on to Xianyang, he had to travel north to fight another battle.

The troops at Xianyang were mobilized to do battle against Xiangyu, leaving Xianyang unguarded. Liu Bang, the opportunist he was, was able to enter the unprotected Guanzhong region easily and was able to ‘conquer’ Xianyang while Xiang Yu was still busy dealing with the main Qin forces.

Liu Bang also used his wits and political knavery in the process. He ordered that his army was NOT to harm or loot from the people in Xianyang and Guanzhong, winning over the hearts of the local.

Xiang Yu, on the other hand, was simply brutal and killed all who stood in his path.

《秦始. 项羽本纪》

項羽遂西,屠燒咸陽秦宮室,所過無不殘破。秦人大失望,然恐,不敢不服耳 (4)

When Xiang Yu learned that Liu Bang had reached Xianyang before he did, he was incensed and many believe that this incident buried the roots of disdain. The two would later become arch enemies.

《史記·高祖本紀》

或說沛公曰:「秦富十倍天下,地形彊。今聞章邯降項羽,項羽乃號為雍王,王關中。今則來,沛公恐不得有此。可急使兵守函谷關,無內諸侯軍,稍徵關中兵以自益,距之。」沛公然其計,從之。十一月中,項羽果率諸侯兵西,欲入關,關門閉。聞沛公已定關中,大怒,使黥布等攻破函谷關。 (1)

As Liu Bei was able to get to Guanzhong before Xiang Yu, and Liu Bei was represented by Red, many people have used this incident to explain why Red moves first in Xiangqi and why it is better to use wits to win a battle rather than brute force.

Why does the King in Xiangqi not allowed to meet each other face to face in the same file?

The Royal Rule or Rule of the Flying Kings in some older literature is a unique rule in Xiangqi. It states that the Kings of the opposing colors are not allowed to meet in the same file without any intervening piece.

This rule is supposedly based on an encounter between Liu Bang and Xiang Yu. As neither faction could gain the upper-hand, the war between the two dragged on and the civilians were in despair. Xiang Yu decided to challenge Liu Bang to a one on one battle to decide who was the strongest and end the war.

Liu Bang refused to the challenge and claimed that he preferred to win with his wits and not with brute force. This incident would be used later as the reason why the Kings do not face each other directly in Xiangqi.

But there is more…

Later, Liu Bang would heckle at Xiang Yu as they stood on opposite sides of the Guang Wu Mountains (广武山 guǎng wǔ shān), counting the ten ‘crimes’ that Xiang Yu had committed. Finally, an incensed Xiang Yu could take it no more and shot an arrow at Liu Bang. The arrow hit Liu Bang in the chest but Liu Bang managed to survive.

The passages given below are from different annals in the Records of the Grand Historian that mentioned the incident.

《史記·項羽本紀》

楚漢久相持未決,丁壯苦軍旅,老弱罷轉漕。項王謂漢王曰:「天下匈匈數歲者,徒以吾兩人耳,願與漢王挑戰決雌雄,毋徒苦天下之民父子為也。」漢王笑謝曰:「吾寧鬬智,不能鬬力。」項王令壯士出挑戰。漢有善騎射者樓煩,楚挑戰三合,樓煩輒射殺之。項王大怒,乃自被甲持戟挑戰。樓煩欲射之,項王瞋目叱之,樓煩目不敢視,手不敢發,遂走還入壁,不敢復出。漢王使人閒問之,乃項王也。漢王大驚。於是項王乃即漢王相與臨廣武閒而語。漢王數之,項王怒,欲一戰。漢王不聽,項王伏弩射中漢王。漢王傷,走入成皋。

《史記·高祖本紀》

楚漢久相持未決,丁壯苦軍旅,老弱罷轉馕。漢王項羽相與臨廣武之閒而語。項羽欲與漢王獨身挑戰。漢王數項羽曰:「始與項羽俱受命懷王,曰先入定關中者王之,項羽負約,王我於蜀漢,罪一。秦項羽矯殺卿子冠軍而自尊,罪二。項羽已救趙,當還報,而擅劫諸侯兵入關,罪三。懷王約入秦無暴掠,項羽燒秦宮室,掘始皇帝冢,私收其財物,罪四。又彊殺秦降王子嬰,罪五。詐阬秦子弟新安二十萬,王其將,罪六。項羽皆王諸將善地,而徙逐故主,令臣下爭叛逆,罪七。項羽出逐義帝彭城,自都之,奪韓王地,并王梁楚,多自予,罪八。項羽使人陰弒義帝江南,罪九。夫為人臣而弒其主,殺已降,為政不平,主約不信,天下所不容,大逆無道,罪十也。吾以義兵從諸侯誅殘賊,使刑餘罪人擊殺項羽,何苦乃與公挑戰!」項羽大怒,伏弩射中漢王。漢王傷匈,乃捫足曰:「虜中吾指!」漢王病創臥,張良彊請漢王起行勞軍,以安士卒,毋令楚乘勝於漢。漢王出行軍,病甚,因馳入成皋。 (1)

Because Liu Bang refused to meet Xiang Yu in a one-on-one combat, and he was injured by Xiang Yu’s arrow, this historical incident was used to explain the Royal Rule or the Rule of the Flying Kings as it was known in the past.

Diagram 3 Red moves first in Xiangqi. Picture Courtesy of Rick Knowlton of AncientChess.com.

Why the Pawns cannot retreat after crossing the river?

The incident of Xiang Yu breaking the pots and sinking the boats is used to explain the phenomena as to why the Pawns are not allowed to retreat after crossing the river in Xiangqi. The incident later became the Chinese idiom 破釜沉舟(pò fǔ chén zhōu) which is used to describe a person as being determined to achieve a goal.

In a nutshell, Xiang Yu once led an army to one of the battles to exterminate the Qin dynasty. As he had no support, he led his troops across a river, and then ordered his men to break all the pots for cooking food. The boats that ferried them across the river were also sank. At that time, they had only three days worth of ration. It was a do-or-die situation as there was no return. Pushed to the brink, Xiang Yu and his men fought like the possessed and won a decisive war against an enemy with much more men. It was said that one soldier from Xiang Yu’s army could take on ten of the enemy soldiers. Xiang Yu would strike fear and make his name known.

The original passage from the Annals of Xiang Yu in the Records of the Grand Historian is given below.

《史記·項羽本紀》

项羽乃悉引兵渡河,皆沈船,破釜甑,烧庐舍,持三日粮,以示士卒必死,无一还心。于是至则围王离,与秦军遇,九战,绝其甬道,大破之,杀苏角,虏王离。涉闲不降楚,自烧杀。当是时,楚兵冠诸侯。诸侯军救钜鹿下者十馀壁,莫敢纵兵。及楚击秦,诸将皆从壁上观。楚战士无不一以当十,楚兵呼声动天,诸侯军无不人人惴恐。于是已破秦军,项羽召见诸侯将,入辕门,无不膝行而前,莫敢仰视。项羽由是始为诸侯上将军,诸侯皆属焉。 (4)

Xiang Yu’s determination to win is one of the reasons why he has been hailed as one of the bravest heroes in China for centuries. The fact that he pushed himself to the brink and severed any escape routes that he and his men might have was later used to explain why the Pawns were not allowed to retreat once they crossed the river.

Afterthoughts

There are many more anecdotes that originated from the Chu-Han Contention. Indeed, this period of history was so inspiring that many Xiangqi endgame compositions found in the Ming Dynasty ancient manual, Elegant Pastime Manual, had references or were simply inspired by the various events that happened during this time.

Unfortunately, the validity of these explanations to prove that Xiangqi was invented during this period of time remains controversial as there are no other supporting evidence. They are very persuasive in a sense but concrete evidence is still lacking.

The author prefers to view these anecdotes and incidents as part of the rich culture of Xiangqi.

References

1. (西汉)司马迁. 先秦兩漢 -> 史書 -> 史記 -> 本紀 -> 高祖本紀. 諸子百家. [Online] [Cited: Jul 12, 2021.] https://ctext.org/shiji/gao-zu-ben-ji/zh.

2. 周, 家森. 象棋与棋话 第三版. s.l. : 世界书局印行, 1947, 民国36年. No ISBN.

3. (西汉)司马迁. Pre-Qin and Han -> Histories -> Shiji -> Annals -> 秦始皇本纪. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Dec 21, 2019.] https://ctext.org/shiji/qin-shi-huang-ben-ji/ens.

4. —. Pre-Qin and Han -> Histories -> Shiji -> Annals -> Annals of Xiang Yu. 诸子百家 Chinese Text Project. [Online] [Cited: Dec 21, 2019.] https://ctext.org/shiji/xiang-yu-ben-ji/ens.

5. 李, 松福. 象棋史话. 北京 : 新华书店北京发行所, 1981. 7015.1939.

6. 张, 如安. 中国象棋史. 北京 : 团结出版社, 1998. 7-80130-170-6.

7. 张, 展. 象棋人生. 北京 : 经济管理出版社, 2012. 9787509621394 .

8. contributors, Wikipedia. Chu–Han Contention. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. [Online] Page Version ID: 1027946672, June 10, 2021. [Cited: July 6th, 2021.] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chu%E2%80%93Han_Contention&oldid=1027946672.

9. 陈, 贤玲. 象棋方程 . [ed.] 跃中 李. 北京 : 中国社会出版社, 2009.2. 978-7-5087-2456-0.

10. Gernet, Jacques. A History of Chinese Civilization Second Edition. [trans.] J.R. Foster and Charles Hartman. s.l. : Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1996. 0-521-49712-4.